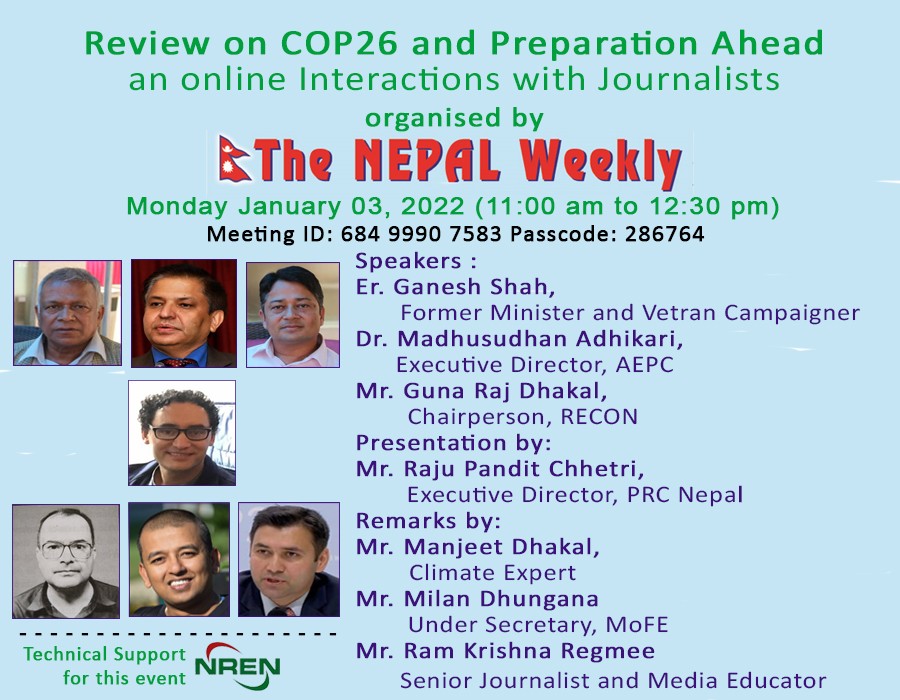

The Nepal Weekly

The Nepal Weekly  December 17, 2024

December 17, 2024

Leading a five- member Nepali delegation to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the Hague, Minister for Foreign Affairs Dr Arzu Rana Deuba has presented Nepal’s position on December 9 in the ongoing public hearings on the ‘Obligations of States in respect of Climate Change’. The oral proceedings are being held at the Court since 2ndDecember 2, with the target to complete by 12thDecember.

Minister Rana Deuba is accompanied by Udaya Raj Sapkota, Secretary of the Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs, and other officials from the MoFA and the Embassy of Nepal in Brussels, as mentioned in a press release issued by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA) the other day.

The hearing at the ICJ are instituted by the Court pursuant to the United Nations General Assembly Resolution A/RES/77/276, which requested the Court to render an advisory opinion on the obligations of States in respect of climate change. An advisory opinion is a non-binding legal advice provided to the UN or a specialized agency by the ICJ, in accordance with Article 96 of the UN Charter.

In The Hague, Nepal has renewed calls for climate justice to ameliorate the harsh suffering that climate change has brought to the lives of Nepali people.

Drawing the attention of the International Court of Justice to the impacts of climate change, Nepal made a strong plea for climate justice to alleviate the suffering that Nepali citizens.

Making an oral presentation to the court’s public hearings on the ‘Obligations of States in respect of Climate Change’ last week, Minister Arzu Rana Deuba said global warming and consequent climate change increasingly threaten Nepal’s snow-capped mountains and glaciers.

“We are bearing the brunt of the impacts of climate change in a disproportionate manner,” said Rana Deuba “We have been penalised for the mistakes we never made, for the crimes we never committed,” she added

The worst impacts of the climate crisis have been apparent in Nepal for several years. Mountains are melting, and glacial lakes have been bursting and vanishing at record rates, with one-third of them lost in just three decades, Rana Deuba added. Monsoons, storms and landslides are growing in force and ferocity—sweeping away crops, livestock and entire villages—decimating economies and ruining lives.

Despite playing a crucial role in maintaining climate balance, supporting ecosystems, and preserving biodiversity, Nepal remains vulnerable due to its geographical circumstances and relatively low level of development, Rana Deuba said.

Speaking on human rights law-related obligations of states in connection with climate change, Rana Deuba highlighted Nepal’s position that many vulnerable states were not able to meet their obligations under international human rights law as actions and emissions arising from beyond their territories also affected the specific rights of their citizens.

It is to recall that, in September 2021, the Pacific island of Vanuatu announced its intention to seek an advisory opinion from the ICJ on climate change. It explained that this initiative, pushed for by the youth group Pacific Island Students Fighting Climate Change, was necessitated by its vulnerability and of other small island developing States to climate change and the need for increased action to address the global climate crisis.

The hearing aims to set a legal framework for how countries should tackle climate change. It is part of the court’s advisory opinion process, which will clarify states’ legal obligations under international law and the consequences for breaching them.

This climate change case started in 2021 when a group of law students lobbied the government of Vanuatu, a tiny South Pacific island nation threatened by rising sea levels, to approach the court. They wanted the court to issue an advisory opinion on what countries should be compelled to do to prevent climate change.

An advisory opinion is advice from the court to the United Nations on how best to apply international law on a specific matter.

Other countries – 131 of them – supported Vanuatu and drafted a resolution which the United Nations general assembly adopted.

The resolution said that the general assembly then asked the International Court of Justice to decide what legal obligations every government has to prevent climate change.

The court will decide (a) governments’ obligations under international law to protect the climate system and other parts of the environment from greenhouse gas emissions, now and in the future, and (b) the legal consequences for governments that fail to do this and cause harm to future generations and other states (especially small island nations that are affected by rising sea levels).

First, the wellbeing of present and future generations needs an immediate global response to climate change. This will be the first time that a legal precedent is set under international law, setting out what all governments must do to prevent further global warming.

Second, the case will clarify the legal approach to human rights problems caused by climate change. For example, in the landmark Dutch Urgenda decision in December 2019, the Netherlands supreme court established a legal duty for the Netherlands government to reduce greenhouse gas emissions because they cause climate change, which affects people’s human rights. Following this case, human rights based climate lawsuits spread all over the world.

The Inter-American Court of Human Rights held hearings for its advisory opinion on the climate emergency and human rights in April 2024. In the same month, the European Court of Human Rights heard its very first human rights climate cases. One ruling already states that a lack of climate action by governments violates human rights. The International Tribune for the Land and the Sea has also said that climate change “raises human rights concerns”.

Third, the impact of the world’s highest court lending its voice to the climate crisis will not only be felt by the countries directly involved, but will influence all countries.

This could open the door for transnational climate litigation, especially in matters of the sea and trade, and for corporate climate cases.

Fourth, this case is a powerful tool that youth, non-governmental organisations, civil society and climate justice activists can use in campaigns.

Finally, this advisory opinion will highlight the damage caused by climate change to developing countries and small island states.

This opinion could clarify whether and how developed nations are legally required to mitigate climate impacts, assist vulnerable countries, and uphold human rights in the context of climate change.

The international community will be strictly required to act on the recommendations that emerge from the court’s opinion. This will make global climate governance stronger (climate change affects the world and the world needs to work together in limiting it). It could lead to more international co-operation and to climate finance being made available for developing countries.